‘400

Ballate, Barzellette, Strambotti,

the Italian music in 15th century

The 15th edition of the International Course of Medieval Music coincides with 40 years of Micrologus and 15 years of the Centro Studi Adolfo Broegg. This year’s theme will be dedicated to the musical forms of Italian Humanism. In the Italy of the 15th century, many musical genres and styles coexisted, given the great passion of the ruling families on the peninsula for music of the Oltremontani. The chapel masters of the wealthiest and most prestigious courts, such as the Aragonese court of Naples, the Este in Ferrara, the Bentivoglio in Bologna, the Medici in Florence, and the Sforza in Milan, as well as the papal court, had Flemish or

Northern French musicians in their service. The Burgundian court of Philip the Good (1420-1467) was one of the most important cultural centers in Europe, and many of the composers who passed through there were the same ones who brought a vast repertoire to Italy, as evidenced by handwritten sources, mainly Franco-Flemish. Distinguished musicologists since the early 1950s have tried to understand why the 15th century seemed to be a century without Italian music and poetry. The title of the book “Il segreto del quattrocento” [The Secret of the Quattrocento] by Torrefranca summarizes this “mystery” which other scholars, notably Nino Pirrotta, have tried to investigate. The Sicilian musicologist analyzed the possible reasons for this apparent gap in early modern Italian music. Thanks to his original intuition affirming the central role of oral tradition, certain repertoires, even regional ones such as siciliane and justiniane, can be highlighted, defining a true Italian style instead. Pirrotta argued that Italian repertoires were performed, but that a large part of them went unnotated, given the improvisational tradition and unwritten tradition that characterized that historical period. In his words,

“The music from which we make history, the written tradition of music, may be likened to the visible tip of an iceberg, most of which is submerged and invisible. The visible tip certainly merits our attention, because ‘it is all that remains of the past and because it represents the most consciously elaborated portion, but in our assessments we should always keep in mind the seven-eighths of the iceberg that remain sub- merged: the music of the unwritten tradition.“[2]

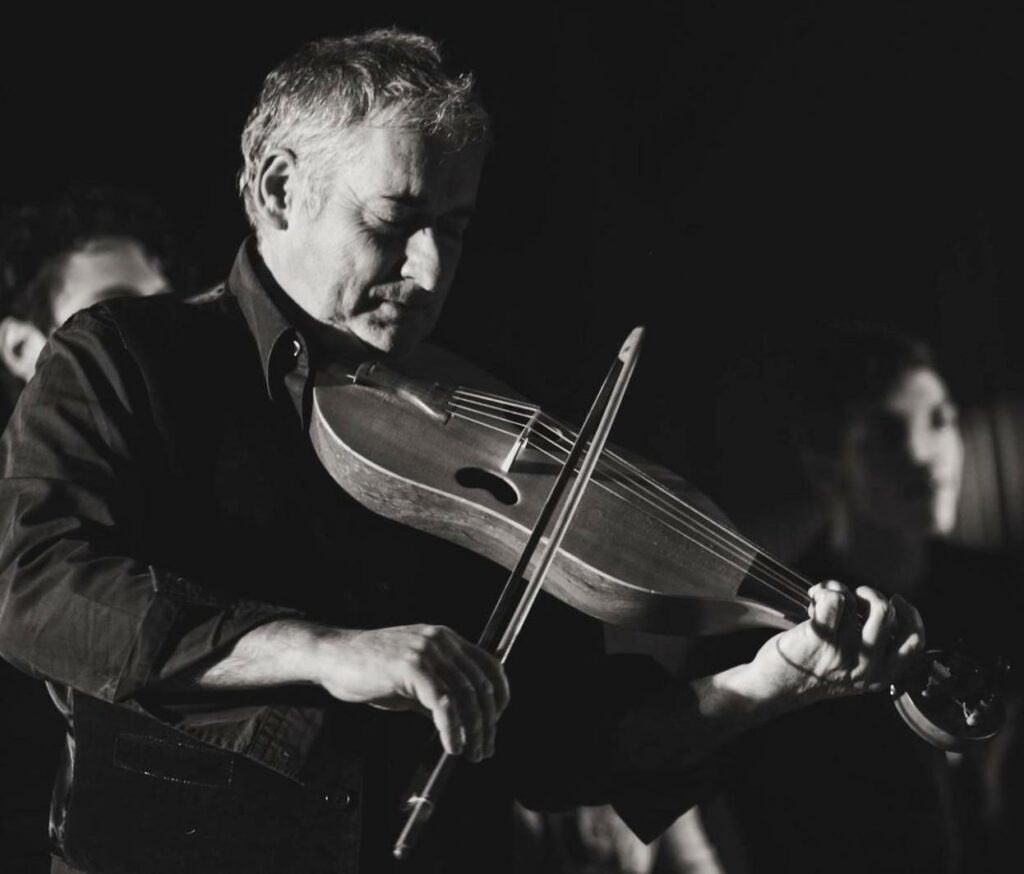

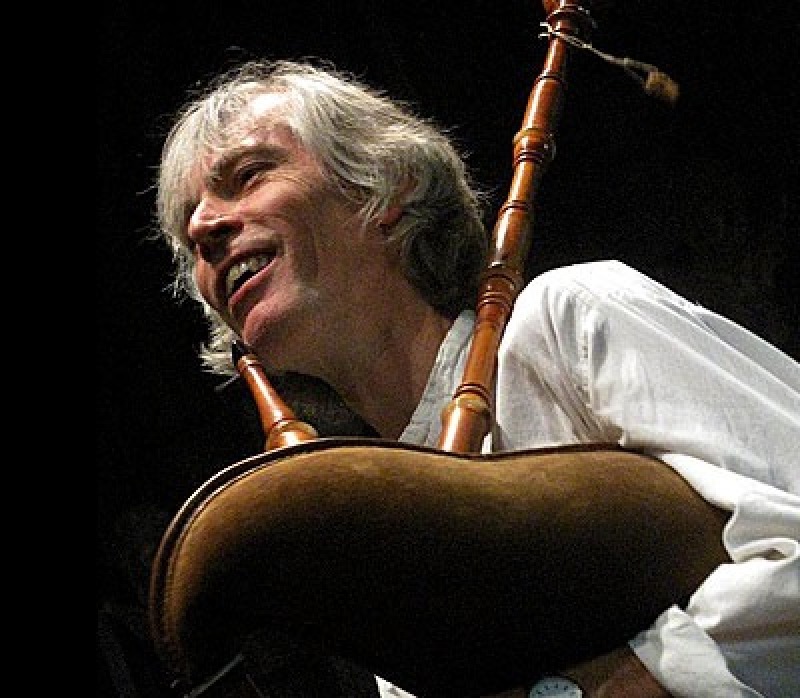

Despite the predominance of Franco-Flemish music in Italian sources, a large number of Italian-texted pieces have been transmitted. Ballate, barzellette, strambotti, and then frottole, these forms sometimes follow the compositional rules brought by theorists from Franco-Flemish countries, but very often they have a more chordal structure that follows the poetic text; the counterpoint is often simplified, suggesting a practice of monodic singing accompanied by an impromptu accompaniment on a stringed instrument. The lira da braccio, the lute and the cetra were the instruments preferred by the humanists, who saw in them the ancient classical tradition of singing to the lyre of Orpheus and Apollo. They were less interested in those “little signs of music” that characterized the rigor of polyphonic singing and ornate counterpoint, and instead were more attracted to singing strambotti, sonetti and capituli to simple melodies to better understand the sense of the text. The differences between Italian and Franco-Flemish repertoires will be analyzed in the light of the treatises of the time, with a focus on Johannes Tinctoris’ treatise “De inventione et usu musice” (c. 1480-1483).

[1] Nino Pirrotta,’Musica tra Medioevo e Rinascimento’, Einaudi, Torino 1984, p. 177

[2] Nino Pirrotta, “The Oral and Written Traditions of Music,” Music and Culture in Italy from the Middle Ages to the Baroque (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 72.